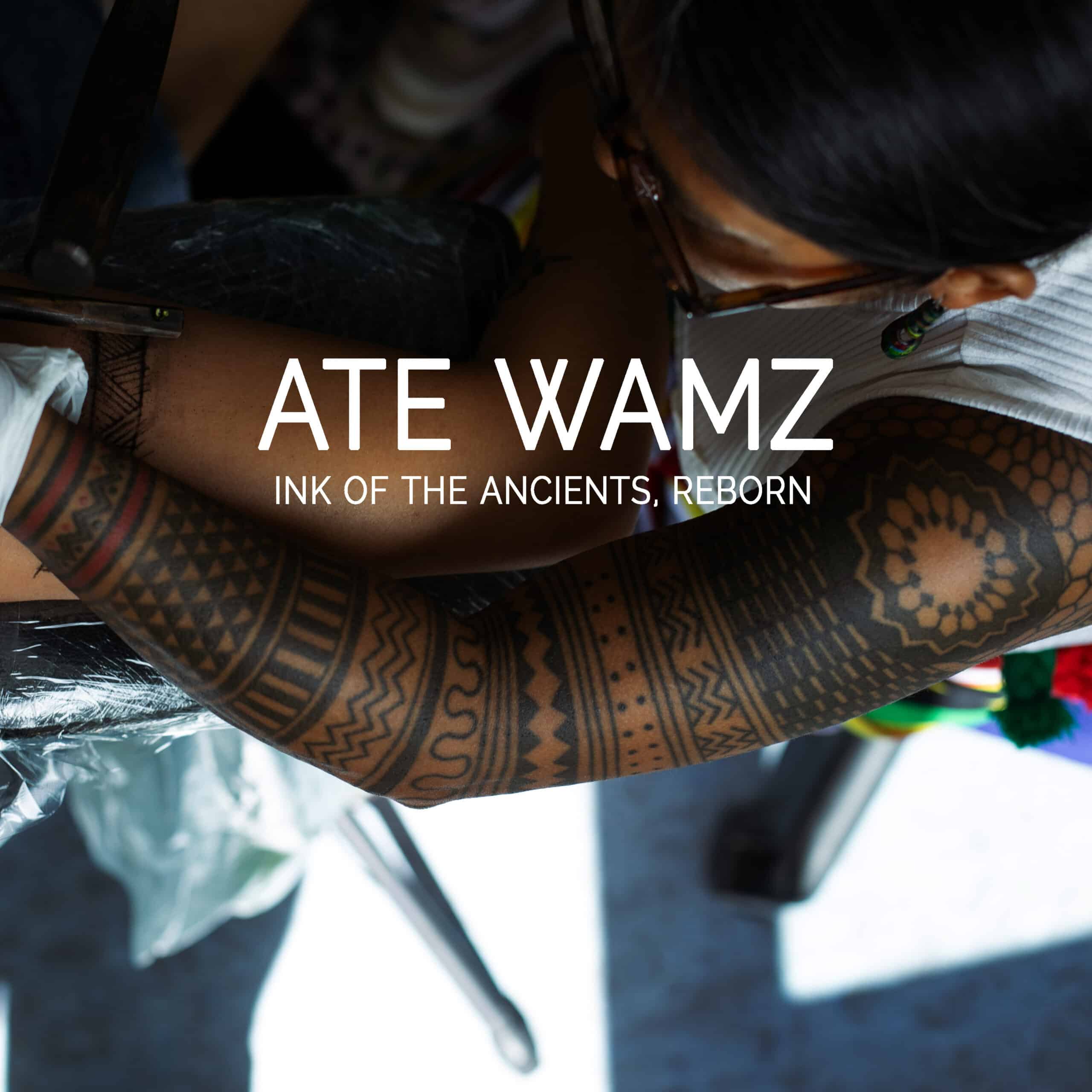

By Jeminah Birkner | Isla Magazine

Long ago, when the mountains still whispered and the rivers carried the names of spirits, there lived women who wore their stories on their skin. Each line was a prayer, each dot a declaration. These were not mere tattoos; they were contracts between flesh and ancestor, memory and myth.

For a time, the ink fell silent.

But in the quiet village pathways of Benguet, where the air hangs thick with pine and lore, the ink has begun to speak again. At the center of this revival walks Ate Wamz, not merely a tattoo artist, but a ‘mambabatok‘, a keeper of sacred lines, a bridge between past and present.

She does not call herself chosen; the ancestors did.

The calling came not as a vision, but a gentle ache—a pull toward the soot-stained rituals her grandfathers once practiced as manbunong (shamans). Raised in the embrace of her Kankanaey mother’s culture, she was no stranger to the canao, the feast of spirits where chickens were offered and omens read from bile.

Yet the art of tattooing, once worn proudly by women and warriors alike, was cloaked in silence. The missionaries had named it sin. The skin, once a sacred scroll, became blank.

When Wamz heard whispers of Apo Anno, the tattooed mummy of the Kalanguya, Kankana-ey and Ibaloi people, preserved in a cave not far from her ancestral land in Buguias, the ink within her stirred.

“It wasn’t something I planned to do,” she would later say. “I became an advocate for cultural revival first. But the ink found me. It felt like I was reclaiming something that was always mine.”

Without formal training, she began. Alone, but not truly alone. Her hands remembered what her lineage had buried. She did not copy; she listened, to the stories, to the mountains, to the people who came with grief etched into their bones and healing waiting under the skin.

Her tools were traditional, thorns from the lemon tree, soot from ancestral firewood, mixed with sacred water carried from Mt. Pulag. “This ink,” she said once, mixing it with care, “is not just pigment. It is memory, it is spirit, it is place.” And then came the people—some from the city, some from distant islands, some who had never seen their grandmother’s village, and some who had forgotten their dialect. They came not for beauty, but for belonging.

“Before I tattoo, I listen. Each person brings a story. Sometimes pain, sometimes joy. The design comes from that exchange. I don’t choose randomly; it is always guided.”

A woman grieving the loss of her mother. A man searching for connection. A queer youth reclaiming a lineage they were told they didn’t belong to. For each, Ate Wamz found a symbol, a fern for healing, a dog for loyalty, a river for rebirth. She pulled from the well of Benguet, from Kankanaey spirals and Kalanguya lines once etched onto arms to signify recovery after illness.

Other artists came with machines and trends. Wamz came with silence, ceremony, and a deep respect for what had been lost.

“Some people ask me, how is this different from what others do? I say, this is not a job. This is a rite. I don’t just tattoo—I perform healing. I ask the spirits for guidance. Every dot I place is a prayer.”

She studied other tribes too—the stars of Bontoc, the rivers of Ifugao, the fire symbols of Kalinga. But her compass was always the land she came from. Benguet may not have had the spotlight of Kalinga’s famed Apo Whang-Od, but it held stories just as deep, if not more hidden. “I’m the first to bring back traditional tattooing in Benguet after it was silenced for centuries,” she said, not with pride, but with gravity. “This isn’t fashion. This is a resurrection.”

To tattoo, for Ate Wamz, is to walk between worlds. She speaks often of guidance, of sensing energy, of knowing when not to mark someone. Of dreams where ancestors offer designs, or moments when clients weep not from pain, but from release.

“Sometimes, the design reveals something they didn’t know they were carrying. Afterward, they feel lighter. It’s not just the skin that’s changed, it’s the spirit.”

In her practice, not all are accepted. She turns away those who come seeking vanity. “If you’re just here for aesthetics, you’re not ready,” she tells them. “The ink must mean something. You must honor it.”

She doesn’t teach students in the usual sense. “This art chooses its vessel,” she says. “It’s not just about skill, it’s about alignment. It will reveal itself when the time is right.” Her tattoos are not loud, yet they speak. They echo the chants of the elders, the laughter of the rice terraces, the sorrow of a culture that nearly forgot itself, and the joy of remembering.

“My hope is that our youth wear our culture with pride again. That they see our tattoos not as something primitive or embarrassing, but as something divine. We are not broken. We are waking up.”

And so the ink flows again, along collarbones, down arms, across shoulders. It whispers of grandmothers and warriors, of illness survived, of identities reclaimed.

In the hand of Ate Wamz, the mambabatok, each mark is a seed. From that seed grows a garden of remembrance, one line, one soul, one story at a time.

About Ate Wamz

Wamz Pashallan is a Kankanaey and Kalanguya cultural tattoo practitioner based in Benguet, Philippines. Known as a modern-day mambabatok, she is at the forefront of reviving the traditional tattooing practices of the Igorot people, particularly those from Benguet whose tattoo histories were largely undocumented. Her work blends ancestral guidance, ethnographic research, and spiritual intuition. She uses traditional hand-tapping tools and natural ink made from soot and water sourced from sacred sites. Ate Wamz also advocates for Indigenous cultural education and regularly speaks on decolonizing beauty, identity, and body ownership through traditional art. Her practice serves as both healing and reconnection, especially for diasporic Filipinos and Indigenous youth.

BATEK

Batek is a traditional tattooing practice in the Philippines, particularly among indigenous communities in the Cordillera region, which includes Benguet. This slow and deliberate process requires skill and precision, tapping rhythmically and carefully to create the desired design.

Next Events:

Invitation fr. Oslo Tattoo Show

Wilma Gaspili, also known as Ate Wamz, is an indigenous tattoo artist and advocate dedicated to preserving and promoting the cultural heritage of the Cordillera region globally. Her work focuses on raising awareness and protecting the traditional art of Batek tattooing, specifically through her meticulous reproduction of ancestral designs using traditional methods and pigments. As a member of the Kankana-ey and Kalanguya tribes of Benguet, her personal connection to this vanishing cultural practice fuels her commitment to its preservation and wider appreciation, a commitment she shares around the globe.

Book with her @atewamz

Or meet her in person at @oslotattooshow

![]() 15-16-17 AUGUST

15-16-17 AUGUST

![]() Oslo Event Hub. Dronningensgate 4.

Oslo Event Hub. Dronningensgate 4.

OSLO GET READY!