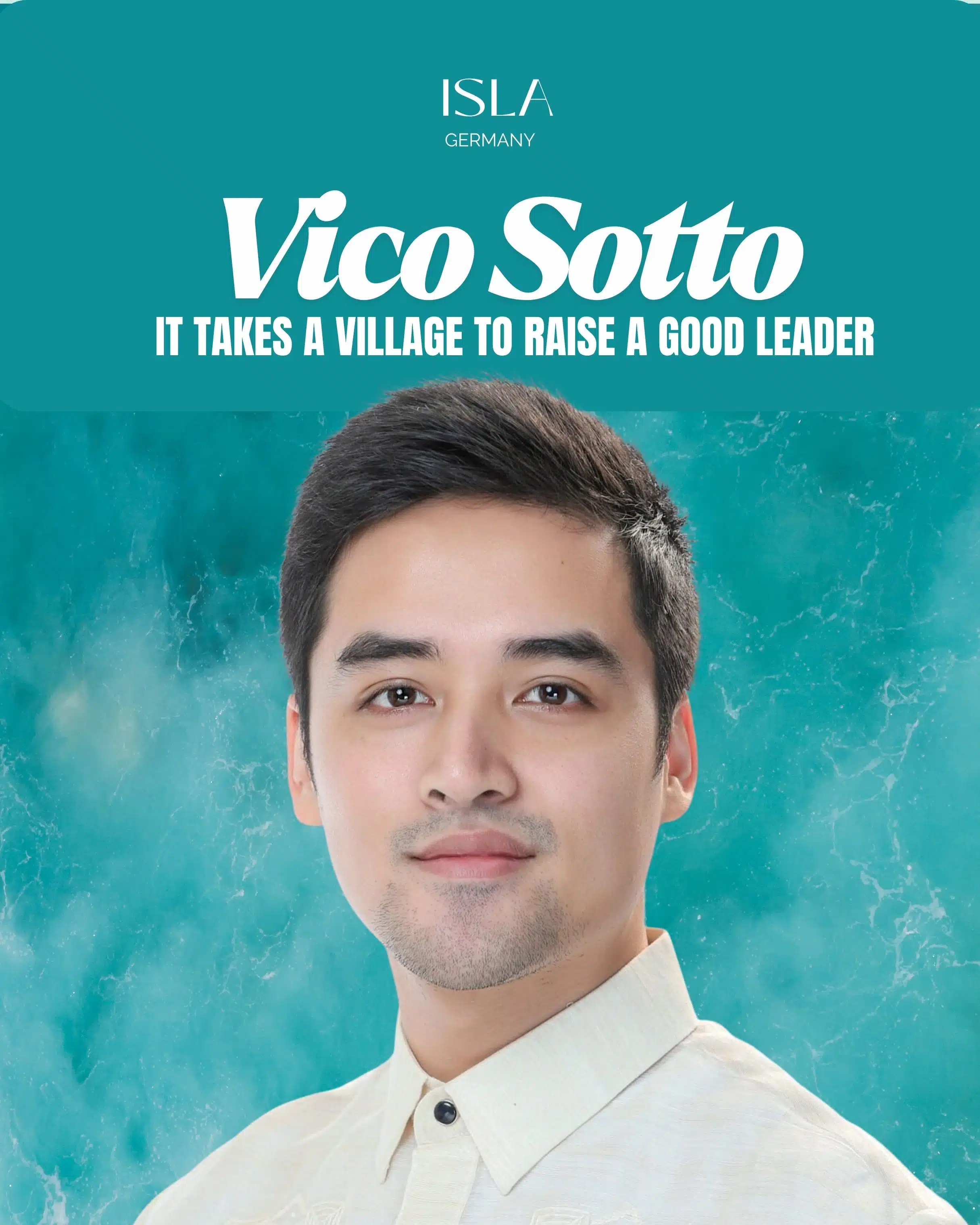

By Jem Birkner | Isla Magazine Germany

There are rare moments in Philippine politics when someone appears and reminds us what public service should look like. Not as theater. Not as inheritance. But as replicable systems in place.

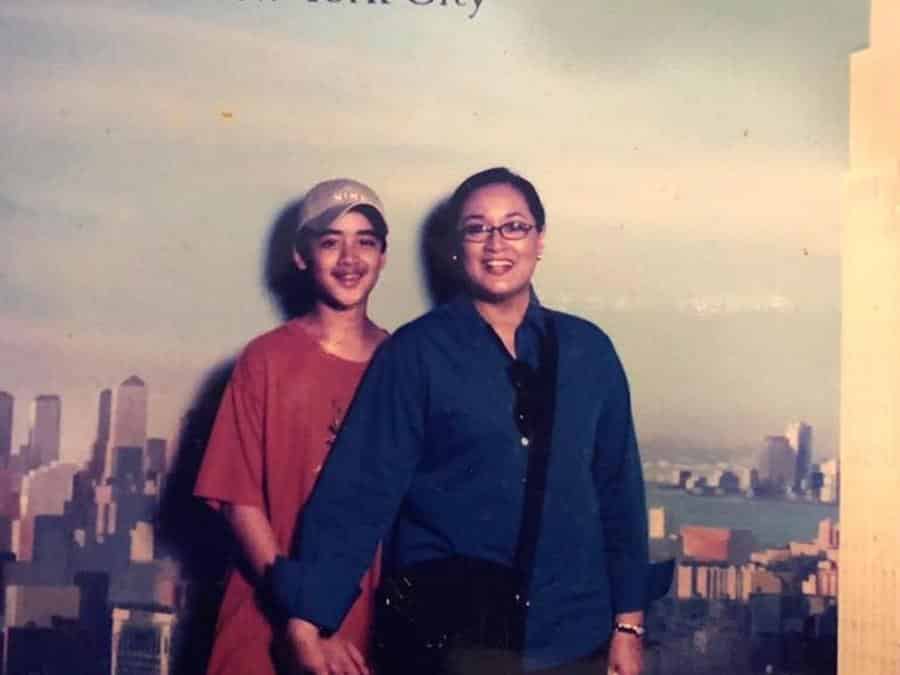

I first saw Vico Sotto not in a campaign rally or a government event, we were both young kids attending kids church, at Victory Christian Fellowship in Fort Bonifacio, he is around two or three years younger, and I was already doing kids church assisting, so he was still considered then – one of the “kids”. He was quiet, not shy, just observant. My aunt, who happens to be good friends with his mother, Ms. Connie Reyes, are both women of faith and have a deep devotion to prayer. He grew up with a mother who is deeply prayerful, grounded, and strong. Seeing him there, I now understand what we often admire in Vico, his calm integrity, his humility, his consistency — may well be rooted in a home that values faith and quiet conviction more than fame. It took a village to raise the man he is now, pastors, youth leaders, a community of people who spoke truth, even when it was uncomfortable. Values bounded by the word of God, not taught as “religion” but a standard way of life.

In that simple moment, I caught a glimpse of the foundation behind the man who would later become one of the most respected mayors in the Philippines.

Vico’s rise wasn’t built on political dynasty or celebrity clout, though he could easily have leaned on either. Instead, he walked a path that few with his background ever dare to take, into the chaotic, often cynical world of Philippine governance. His leadership, however, feels like an antidote to that cynicism. He represents the kind of politics the modern Filipino, connected, discerning, and exhausted by empty promises, has long been waiting for.

His brand of leadership is data-driven, transparent, and human-centered. It’s rooted not in charisma but in competence. Where traditional politicians rely on spectacle, Sotto relies on systems. He champions reforms that are not just ethical but efficient, reforms that turn lofty rhetoric into measurable results.

And the results are visible.

Under his watch, Pasig City transformed into a model of digital governance. Transactions that once required days of lining up can now be done online. Procurement processes are transparent. Budgets are traceable. Corruption has declined dramatically, with Sotto himself revealing that the city now saves an estimated ₱1 billion annually through proper bidding and clean systems, without raising taxes.

Then there’s his vision for the future, one that’s bold, practical, and rooted in legacy. He recently broke ground for what he calls “the biggest project in Pasig’s history”, a new Pasig City Hall Complex, designed to last a hundred years. It’s not just an administrative building; it’s an ecosystem. The complex will include senior citizens’ zones, children’s play areas, open plazas, and evacuation centers. For Sotto, it’s about infrastructure that uplifts human life, not just government optics.

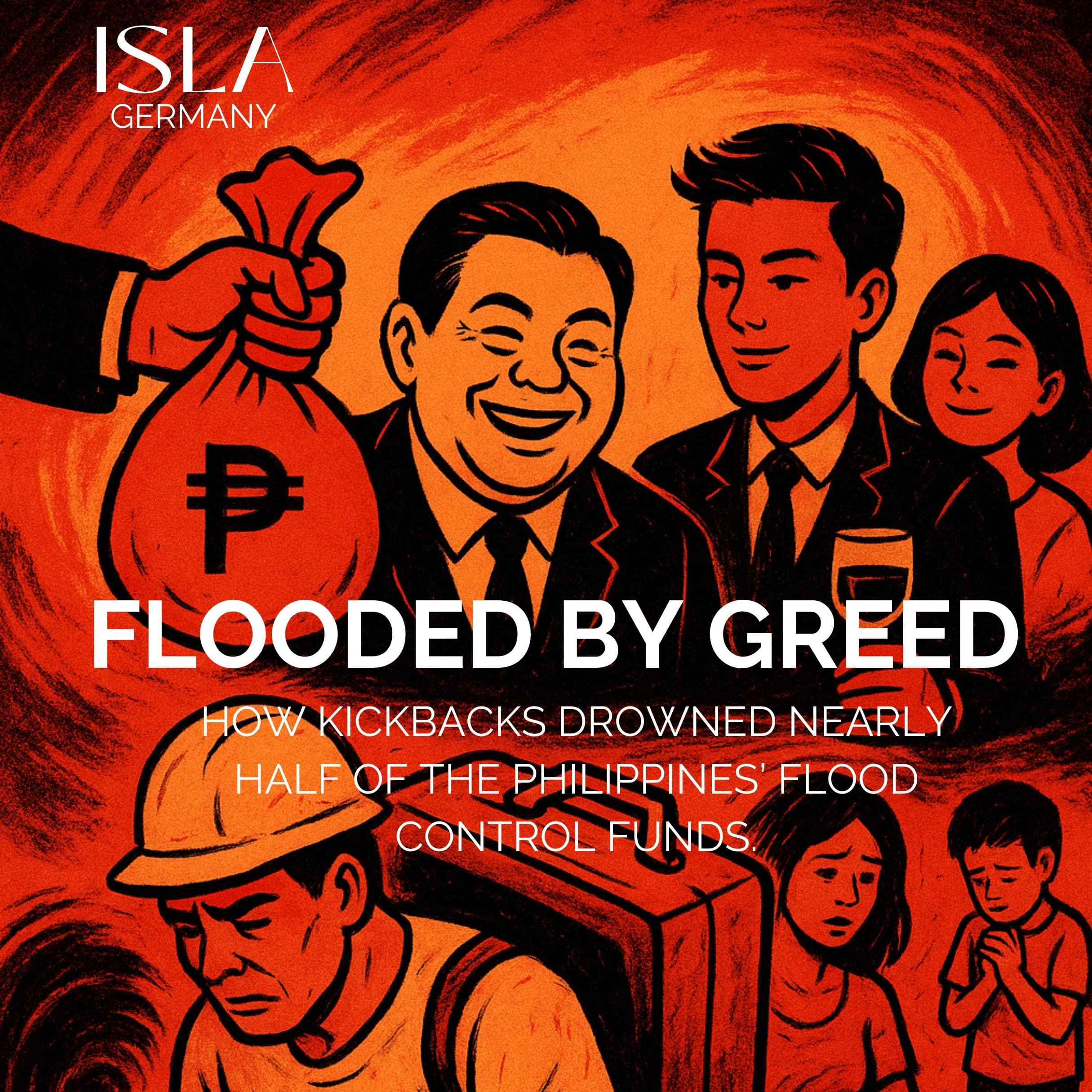

His transparency model runs deeper than press releases. He opened public vetting for flood control projects, invited civil society groups to audit expenditures, and insisted on independent oversight. This is a radical act in a country where “audit” is often synonymous with cover-up. Through online dashboards and citizen engagement, Pasig residents can actually see how and where their taxes are spent.

This approach mirrors what sociologists like Sherry Arnstein and Archon Fung describe as participatory governance, a form of democracy that empowers citizens to become co-authors of reform rather than mere spectators. It also reflects Merilee Grindle’s “Good Enough Governance” theory, which argues that progress is built on achievable, incremental reforms that restore trust in institutions.

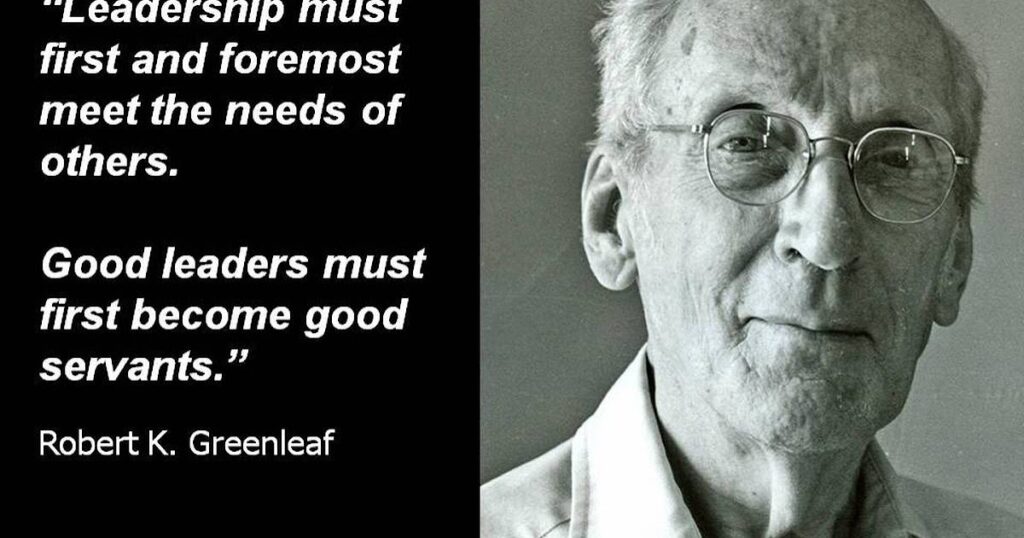

Sotto doesn’t lead like a warlord, nor does he perform like a celebrity. His management philosophy is closer to Robert Greenleaf’s Servant Leadership, where authority comes from service, not dominance. He empowers his staff, many of them young professionals from outside politics, to make decisions, innovate, and question old norms. His meetings are conversations, not monologues.

In the language of leadership studies, this is transformational leadership, as James MacGregor Burns would put it, the kind that raises both leaders and followers to a higher moral plane. In practice, it looks like collaboration, humility, and purpose.

But in essence, it’s something simpler: he listens.

He listens to his people, his data, and his conscience.

His projects reflect the quiet power of listening. The literacy and reading camps launched under his watch improved test scores among Pasig children within a single year. His push for sustainable transport brought e-bikes, solar-powered charging stations, and eco-friendly e-trikes into city operations, a glimpse of what green urban mobility could look like across the Philippines.

And perhaps what strikes me most is how unbothered he seems by the noise. The criticism, the comparisons, the political pressures, they don’t seem to distract him. He just works. Consistently. Quietly. Faithfully.

In a country where leadership is too often mistaken for dominance, Vico Sotto leads through steadiness. He embodies a kind of leadership that doesn’t shout but still commands respect. He proves that good governance doesn’t require theatrics just good teams, working systems, clear data, and the will to do what’s right even when no one is watching.

His mother’s faith and his own integrity are visible in his conduct, calm, deliberate, disciplined. There is something deeply countercultural about that in Philippine politics, where power often corrupts both tone and temperament.

What makes Sotto’s governance revolutionary is not its scale, but its replicability. His reforms can, and should, be mirrored in provincial and national levels. It starts with the same ingredients: transparency, accountability, collaboration, and a redefinition of public office not as power, but stewardship.

It also requires a cultural shift: to stop treating politicians as demi-gods, and start demanding they act as public servants. The Philippines doesn’t need saviors. It needs systems that work. It needs leaders who serve.

Vico Sotto’s example shows that it’s possible, that faith, humility, and intellect can coexist with effective governance. That politics doesn’t have to be dirty to be powerful. And that change, no matter how quiet, can ripple outward, from one city, to one nation, to one future that finally looks like what we’ve always hoped for.

He is, indeed, the golden reformist, not because he glitters in the spotlight, but because he reflects the light of something greater: a generation of Filipinos who are done idolizing politicians, are now finally ready to rebuild something that would last our lifetimes.